Segregation by Law

I recently came across an episode of the Netflix show, "Explained," which tackled explaining the issue of "The Racial Wealth Gap." One of the most compelling stories from the short episode is when Congressman Cory Booker tells the story of his parents' attempt at buying their first home in the late 1960s, which involved a bit of 'bait and switch' in order to accomplish the purchase.

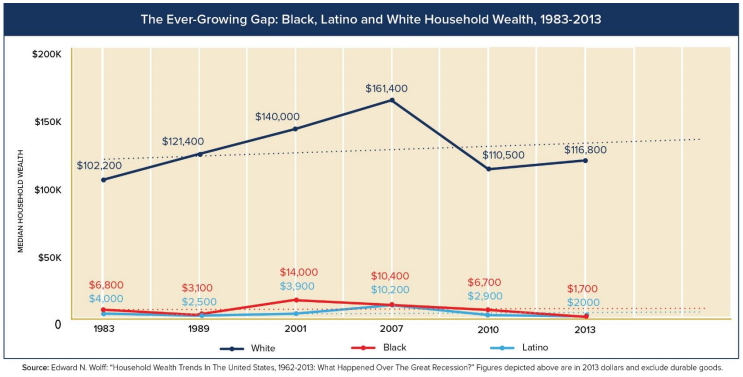

This chart from The Institute for Policy Studies' report, The Road to Zero Wealth, illustrates the massive income gap between white households and minority households:

Rothstein explains how two main policies in The New Deal segregated housing: the Public Works Administration, which built public housing (primarily for middle class white families) during the housing shortage, and the Federal Housing Administration, which provided subsidies to mass production builders and would not insure mortgages to African American families.

This quote represents the intention behind many of the policies of this time. Rothstein cites "85% of the subdivisions built in the New York City metropolitan area in the 1930s and 40s had FHA required restrictive covenants on them." Rothstein goes on to tell story after story detailing the ways the FHA attempted to segregate communities, including requiring a 6 foot wall between a new neighborhood and an older one filled primarily with minority tenants. During his explanation, Rothstein mentions a process called "red lining," in which maps were color-coded to indicate where mortgages were safe. African American neighborhoods were outlined in red to indicate that they were too risky to insure.

This chart from The Institute for Policy Studies' report, The Road to Zero Wealth, illustrates the massive income gap between white households and minority households:

Brian Thompson's article in Forbes goes into more detail about the wealth gap. I also found two additional articles from the Pew Research Center on the topic: How Wealth Has Changed Since the Recession and Findings on the Rise in Income Inequality.

While discussing the "Explained" episode with some of my colleagues, I was directed to the Fresh Air podcast, among other sources which address this issue in a likely less partisan way than the Vox-sponsored show. In this particular Fresh Air episode, "A 'Forgotten History' of How the U.S. Government Segregated America," Terry Gross interviews author Richard Rothstein to discuss how racial inequalities are much more rooted in law than many may realize.

"Incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities."

Popular during this time were Urban Renewal programs, in which African American neighborhoods were demolished to create a new and different area, whether schools, shops, hospitals, or housing for white people. The phrase "Urban Renewal" is not a concept that has disappeared over the years. We still see it occurring every day in pockets of downtown Atlanta.

Rothstein acknowledges there is a "cost of integration," but that the benefits far outweigh them. Continued segregation leads to police confrontation, continued inequality, and lack of upward mobility. He states that he prefers the term 'remedies' to Te-Nehisi Coates' 'reparations.' He explains that remedies encompass policies that serve to desegregate, such as affirmative action programs. When asked how this research has shaped his view of race in America, Rothstein claims:

"If we could understand this history, we might be able to address some of these problems."

Reading in such depth about this topic has been an enlightening experience. It's amazing how much history is left uncovered by school textbooks. I agree with Rothstein's closing statement. It is crucial that we understand the root causes of issues before we can truly make headway in improving the problem.

Comments

Post a Comment